“For the present age, which prefers the sign to the thing signified, the copy to the original, representation to reality, the appearance to the essence… illusion only is sacred, truth profane.”

― Ludwig Feuerbach, 1843

Life on Earth in the twenty-first century is characterized by the near inability to avoid being constantly bombarded by images, day in and day out. No matter where you are, there is more likely than not a television, an advertisement, a magazine, a logo, or a computer screen within your field of vision.

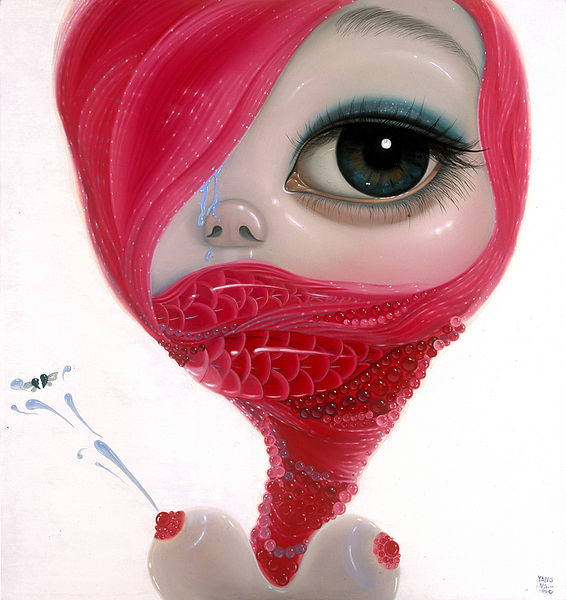

Peach Blossom Thief by Yangna. Photo Credit: Wiki Commons

It does not matter whether you are in a public space or in the comfort of your own home; the endless barrage of imagery is almost inescapable. Airports, libraries, and bars all have televisions plastered on their walls blaring about the latest terrorist attack or the NFC Championship game. Drivers on the highway are always treated to depictions of delicious food or maps of cellular network coverage. Pedestrians in the cities gaze at the figures of celebrities which adorn the faces of entire skyscrapers. And if public spaces are lacking in vivid illustrations, nearly everyone carries around a screen in their pockets with which they can transport themselves into new fantastical worlds at any point in time.

Of course, this isn’t news to anybody. Fears of our transference to an image-based culture have been voiced by many for centuries. Furthermore, hardly anyone can deny that this transition is nearly complete given the daily experience of our lives. What has really been lacking, however, is a widespread recognition of and critical engagement with the consequences of this mode of cultural existence. While many prescient writers, including Ludwig Feuerbach, Daniel Boorstin, Guy Debord, and Neil Postman, have attempted to grapple with the way the image structures the way we think about the world, their voices have largely been ignored, drowned out by the spectacle of modern existence. This is a tragedy, because a large part of the profound alienation and cultural breakdown which we are experiencing today can be attributed to the effects of the image on our minds.

The Ascension of the Image

Before the image dominated our lives, public discourse was primarily mediated by spoken and written language. In the age of the newspaper, the average citizen learned about current events by reading about them and by hearing about them through the grapevine. Education was accomplished almost exclusively through reading and verbal instruction; visual aids and Powerpoint were nowhere to be found. This was the age that gave birth to and characterized the Enlightenment and the Scientific Revolution. Scientific and cultural progress were made by the interplay of various actors making well-reasoned arguments in pamphlets, newsletters, and books. In the political sphere, decisions were made by the citizenry after vigorous debates in the town hall. Candidates for office regularly held debates which often went on for half the day, at which there was enthusiastic attendance. The result of this cultural environment was such that even the average citizen was used to following long arguments and dealing with sophisticated language. Important decisions were often made on the basis of reasoned logic rather than quick, emotional judgments.

Today we have found this type of environment almost completely transformed. If a person even keeps up with the news at all these days, it is often through the medium of 24-hour news networks, which continually display emotional headlines, extravagant graphics, and a ceaseless array of photographs. Education is becoming increasingly characterized by the use of Powerpoint presentations and textbooks filled with fancy diagrams. And while political participation is at an all-time low, what’s left of it is marked by visceral appeals to emotion and simple language. As Chris Hedges writes in his book, Empire of Illusion:

“The Princeton Review analyzed the transcripts of the Gore-Bush debates of 2000, the Clinton-Bush-Perot debates of 1992, the Kennedy-Nixon debate of 1960, and the Lincoln-Douglas debates of 1858. It reviewed these transcripts using a standard vocabulary test that indicates the minimum educational standard needed for a reader to grasp the text. In the Lincoln-Douglas debates, Lincoln spoke at the educational level of an eleventh grader (11.2), and Douglas addressed the crowd using a vocabulary suitable (12.0) for a high-school graduate. In the Kennedy-Nixon debate, the candidates spoke in language accessible to tenth graders. In the 1992 debates, Clinton spoke at a seventh-grade level (7.6), while Bush spoke at a sixth-grade level (6.8), as did Perot (6.3). During the 2000 debates, Bush spoke at a sixth-grade level (6.7) and Gore at a high seventh-grade level (7.6) .27 This obvious decline was, perhaps, raised slightly by Barack Obama in 2008, but the trends above are clear.”

In fact, literacy has declined so much that over half of Americans never read for pleasure at all, a proportion that is increasing rapidly.

The primary catalysts for this transformation were/are the plethora of image-creating and image-reproducing technologies that have appeared within the last two centuries. The arrival of the photograph, combined with the printing press, was of course foundational in the ascension of the image. But as Neil Postman argues in his colossally important work, Amusing Ourselves to Death, the technology which delivered the death blow to language-based culture was the television. Television is a medium, he argues, which relies on constant visual novelty to hold our attention. It is exceedingly difficult to draw viewers to a channel on which reasoned discourse is taking place when the mere press of a button can transport the viewer to the colorful rainforests of South America or to the tranquil beaches of the Caribbean. The way our brains are structured is such that marvelous scenes such as these are almost irresistible to us. Before the television made these visual fantasies possible, people were forced to fill their lives with the slow though often rewarding discourse which language had to offer. Postman writes:

“On television, discourse is conducted largely through visual imagery, which is to say that television gives us a conversation in images, not words. The emergence of the image-manager in the political arena and the concomitant decline of the speech writer attest to the fact that television demands a different kind of content from other media. You cannot do political philosophy on television. Its form works against the content.”

The Internet is another technology which has made the constant delivery of new and exciting images even easier than it was before. YouTube, Netflix, Facebook, and Reddit are all platforms which happily deliver novel images of crazy pranks, stimulating dramas, our friends vacations, and cute kittens daily. Interestingly, the Internet has also given rise to a new form of the article in which images and flashy headlines play a primary role and words are subordinate. One need only look to websites like BuzzFeed and Cracked to get a sense of these so-called “clickbait” articles. Of course, we must also be aware that the Internet, unlike television, can be used for the propagation of language-based discourse, as well. Wikipedia makes written knowledge universally accessible, e-books are widely available across the web, and there are countless blogs just like this one where reason and ideas are still the rule rather than the exception. But because the Internet bloomed in a time when TV was already king, it has been predictably used to perpetuate the extant trend of image-ification.

Appearance and Essence

Even if one grants that our culture is dominated by images, it is probably unclear to many why this should be a problem. At least on the surface of things, it appears that while the image is ever-present in our consciousness, it has not diminished the importance of words in our daily lives. And indeed, images have been present in human society for most of history, in the form of paintings and sculptures. Why should our present age be negatively affected by the supremacy of the image?

In order to understand the answer to this question, one must be able to grasp the distinction between a thing’s appearance and its essence. This distinction is an important one in the history of philosophy, particularly German philosophy. While a thing’s essence is its constitution, what is inherent in it, or the truth of its Being (as Hegel would put it), its appearance is simply a reflection of this essence. As such, it may have many distinct appearances but only one true essence. We cannot always discover the essence of a thing simply by observing its appearance; sometimes we must consider the many appearances of an object or an event to discover the truth about it. Thus, Karl Marx writes: “All science would be superfluous if the outward appearance and the essence of things directly coincided.”

German philosopher Ludwig Feuerbach was among the first to notice that the culture of his age was beginning to become more concerned with the appearances of things than with their essences. The Essence of Christianity, first published in 1841, was Feuerbach’s attempt to critique the religious tendencies of his day. He writes:

“Religion has disappeared, and for it has been substituted, even among Protestants, the appearance of religion – the Church – in order at least that ‘the faith’ may be imparted to the ignorant and indiscriminating multitude.”

For Feuerbach, the Christian religion had devolved into a mere image of its former self. More concerned with maintaining a facade of religiosity and faith to its congregations and outsiders than with imparting to its followers the true essence of its religion, the Church had become an institution confused in all sorts of glaring contradictions and petty rituals. Feuerbach’s perception was an important one, but unfortunately his warnings were heeded by few.

Karl Marx was one of the few who attempted to apply Feuerbach’s insight to other areas of knowledge. His magnum opus Capital was mainly a reaction against the nineteenth century economists who were mostly concerned with maintaining a certain positive appearance of capitalism rather than understanding its true essence. But as the image became more and more important in facilitating our understanding of the world, the gulf between appearance and essence grew ever wider. Because images give us only the appearances of events and objects without teaching us their constitution, we begin to have confused and inconsistent ideas about these things. The more we focus only on appearances, the less effective we become at understanding the world.

Take, for example, the recent tragedy in France involving the mass shooting of journalists at the newspaper Charlie Hebdo. Naturally, the loss of human life is always despicable thing, and the journalists should certainly be mourned. For the average citizen, then, the appearance of million-strong crowds in France and across the world after this event seems to signify a bold stand against the senseless killing of innocent people in the name of a twisted ideology, as well as a strong affirmation of the principle of free speech. This is the image portrayed by the Western media.

When one begins to really think about this situation, however, certain strange contradictions become clear. These Western solidarity marches claim to condemn the murder of twelve innocents in France; yet they have nothing to say when their own governments kill twelve people on the way to a wedding in Yemen with drones. Both events are motivated by ideology. One is an ideology of religious fundamentalism and violent extremism; the other, economic fundamentalism and violent imperialism. Should we not condemn each of these events equally? Furthermore, the crowds claim that they will not be scared out of their right of free speech. And yet nobody seems to complain when rallies against the mass murder of innocents in Gaza are banned in France.

Alienation and The Last Man

Western culture’s obsession with appearances, combined with the proliferation of image-creation technologies, has resulted in an environment in which we are able to construct fantasies to live in rather than experience visceral, immediate reality. Television channels are overflowing with so-called “reality” shows, in which the intimate details of a variety of lives are captured on camera for the world to experience. Video games now offer such an immersive experience that some gamers live primarily in virtual worlds for long stretches of time. Sports have become so ubiquitous that many fans spend all of their free time not only watching the games themselves, but analyses of the games; some even build their own “fantasy” teams with which to compete with others, which requires constant updating of rosters and statistical analysis. The sad truth is that for many Americans, our lives consist mainly in working most of the day for a measly wage, coming home and entering the fantasy of living someone else’s life through the medium of television and computers, and sleeping, ad infinitum.

“In societies where modern conditions of production prevail, all of life presents itself as an immense accumulation of spectacles. Everything that was directly lived has moved away into a representation.”

― Guy Debord, Society of the Spectacle

American historian Daniel Boorstin was acutely aware of this dangerous tendency. In his 1961 book, The Image, he warned that “we risk being the first people in history to have been able to make their illusions so vivid, so persuasive, so ‘realistic’ that they can live in them.” Unfortunately, his premonition has become all too real. Our withdrawal from reality in the West has resulted in a pronounced sense of alienation from which it can be incredibly difficult to recover. One in ten adults in the US have suffered major depression, and diagnoses are growing at “an alarming rate.” Suicides in the US have hit the highest rate in twenty-five years. Driven by deep feelings of insecurity, guilt, and estrangement, people continually turn to drugs, alcohol, diet fads, self-help programs, infidelity, and violence to help heal their wounds. Unfortunately, these distractions often serve to widen the gap between appearance and reality even further.

In a society where the image is king, women learn that only their appearance matters to others. “Others are not concerned with your beliefs, your experiences, or your personality,” scream the Miss USA pageant and the Sports Illustrated swimsuit edition, “the only way to be worth anything is to be sexy.” Men, likewise, spend their time observing images of perfect strength and athleticism. On top of all of this, the incessant pressure on men and women alike to engage in sexual acts before they are even comfortable with their bodies and their sexuality results in even more insecurity.

In schools, where standardized tests can give the appearance of intelligence to those who do well, those who do not begin to view themselves as stupid and worthless. This pressure continues all the way through our childhoods, all the way up until the college admissions process separates those “destined” to be successful from those who are not. Other cultural pressures constantly tell us which TV shows to watch, which kind of music to like, which books to read, and which political views to have. For a society which claims to be founded on individualism, there is an impossible amount of pressure on each individual to conform to certain standards; as a result, many people spend most of their time crafting a certain appearance for themselves rather than discovering the true essence of their individual selves.

Near the end of the nineteenth century, this blog’s figurehead, Friedrich Nietzsche, crafted a category which he called “The Last Man.” The Last Man is characterized by apathy, a lack of passion, and contentedness: “A little poison now and then: that makes for pleasant dreams. And much poison at the end, for a pleasant death. They have their little pleasures for the day, and their little pleasures for the night, but they have a regard for health. ‘We have discovered happiness,’ – say the Last Men, and they blink.” Lamentably, many of us in the West are looking more and more similar to Nietzsche’s Last Man.

Concerned more with image than with truth, we attempt to craft lives which merely look happy from the outside, despite the fact that they are often marked by a deep sadness. We seek easy, ephemeral pleasures rather than striving to achieve true happiness. The supposed mark of success and well-being in the West is that all-knowing god Money; the message is that only material wealth brings peace of mind. But the real essence of happiness is not measured in dollars, cars, or TV screens. It is marked by meaningful relationships, novel experiences of nature and culture, the search for true understanding of the world, and passionate work. The Last Man knows none of these things; his obsession with the false image of happiness distracts him endlessly.

Escaping the Spectacle

Despair not, my fellow humans. The fact that you are here and reading this likely means that you have seen the spectacle of modern existence for the farce that it is. There are many means available to us for escaping the culture of images which has been ingrained in us for most of our lives. Many of the articles on this very blog describe methods by which you can remove yourself from the world of appearances in order to begin to truly understand the world, yourself, and others. These include, but are not limited to: reading books, falling in love, writing, meditating, traveling, seeking novel experiences, creating art, and having discussions about things which are meaningful to you with your friends. All of these activities allow you to live deeply your own life instead of living by proxy. Via these modes of direct experience you can find a truer world and real, lasting contentment.

In your contact with other people, I implore you to fight the destructive power of the image culture. When a friend voices insecurity about the way they look or anxiety about their future success, reassure them that the essence of life does not lie in these fleeting frivolities. Encourage others to follow their passions. Try your hardest to see through corporate media pageant in order to understand the underlying basis of world events. Question everything you’ve been taught, everything you hold dear; no matter how certain you feel of some of your beliefs, they have likely been passed on to you through an ideological lens.

Finally, do not be afraid to love. It is all too easy in this world to hate; acts of violence, strange beliefs, and odd habits are often seen as valid reasons to despise another person. What far too few people understand, however, is that every weird expression or violent action has underlying it billions and billions of lived experiences, relationships, and ideas. The infinite web of human social relations is far too complex for any one person to understand. It is far better to attempt to structure our society in such a way as to foster mutual understanding and love rather than violently oppressing all of those who are different. In order to achieve this, however, we must first remove ourselves from the spectacle of our image-based culture.

If this was jazzy, read the mission and follow us on Twitter.

Nick, thanks for this exceptionally relevant, insightful, and well-written essay. A few more ideas to subvert, disrupt, and/or escape from the spectacle: 1. Don’t watch much TV, especially cable programming with commercials. If you’re going to watch a TV show or film, stream it or watch it on Netflix, etc. 2. Use the add-on AdBlock for Google Chrome to eliminate virtually all advertisements from your online experience. 3. Share content (like this essay) that is primarily language-based, requires sustained attention, and critiques the ways in which images are used (often consciously and maliciously) to distort perception. 4. If you do… Read more »

Thank you Jordan, for inspiring me to write this and inspiring everyone here to live more meaningful lives. I’m sure I speak for everyone when I say that you are one rad dude. As an extra note, I believe that the Internet has the potential to be our most important tool in fighting the culture of appearance. All I can say to everyone is: read, read, read. Never before have so many people had such widespread access to written material. Use it to your advantage to continue your journey of self-discovery and to grapple with the tragedies of life. And… Read more »

The quote you provided by Feuerbach reminded me of another, very similar, quote from the movie The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance”: “This is the West, sir. When the legend becomes fact…print the legend.”, which reminds us how we’ve been well taught to view truth as truly profane. I really, really enjoyed your article, Nick. Several years I started noticing how t.v., video-games, etc., draw you into their realities and how it warps your own. Like so many things that mess you up, these immersions into altered reality are addictions, and like you said, we in the Western societies are… Read more »

I’m glad you liked it, Kronomlo. I love the phrase “digitally-drugged-anti-social husks” 😛 I envy your strength to avoid social media. Even after thinking so deeply about this topic, I still sometimes find myself mindlessly scrolling through Facebook or Reddit and think, what the hell am I doing? It makes me deeply sad to think that so many people spend so much time on social media constructing the appearance of happiness rather than turning that energy towards finding what truly makes them feel fulfilled. But I’m glad that some people are beginning to realize the dangers of this kind of… Read more »

I think one big reason behind ‘mindlessly’ scrolling through websites is just our innate sense of curiosity, since we can’t always go exploring out in the real world and find really important information that we could only find on the internet. Granted, you do learn so much more when you’re outside among people and nature, using all your senses to interact with existence, but there are things in digital realm which are only found here (like this article you wrote), and they will add to the expansion of our education and perception. But yes, spending time constructing a completely different… Read more »

This is really good. Some great insight for our time. There’s so many possible directions this can take. It stands to reason that once someone is bombarded by excessive imagery they will respond in predictable ways. I’m riffing here so pardon my lack of scientific data. 1. Part of the image (or one’s perception the meaning behind it) becomes stored into their subconscious mind and is used occasionally to reinforce/compile worldviews. 2. Their conscious mind becomes desensitized to the excessive stimuli. 3. We press forward in search of something else that might pique our interests. They’ve done some analysis and… Read more »

Hey Jason, glad you enjoyed it. I’m especially interested in your second point: “Their conscious mind becomes desensitized to the excessive stimuli.” I think this is something we have all had experience with. Particularly while watching television, it seems scarily easy to just zone out, go slack-jawed and just receive random information about car insurance rates and cellphone plans even though I normally don’t give a rat’s ass about those kinds of things. I think you’re right to point out that people are almost fanatical about finding other people to blame for their problems. Its certainly something that plagues our… Read more »

“The middle ground is rapidly eroding to various groups who would see their perspectives preached as gospel.” How very well said! The next few lines after that are very true, you need to be either one or the other: left/right, atheist/Christian, fill in blank/fill in blank, and if you’re not one of these, or are one of those, you’re worse than Hitler. Which is also true about “seeking boogeymen to crucify and faultfinding at every corner”, since we can’t face ourselves (cultivating our true Self) we need to both judge and compare everyone else. Which is so insidious because we… Read more »

“In schools, where standardized tests can give the appearance of intelligence to those who do well, those who do not begin to view themselves as stupid and worthless.” This is a terribly important point. Our school systems’ most important goal should be to inspire self-learning, experimentation, debate, and of course, ACTUAL LEARNING. Not enforce some bullshit tests that prove whether or not your kid can memorize facts about certain topics, and then pretend that they are proof of intelligence. One of the main reasons I quit playing computer games, is that in it’s essence, it’s chasing a false sense of… Read more »

Great piece with lots of thoughtful comments. There is a lot of food for thought here. I am pro-capitalism and fairly libertarian but image based technology is getting increasingly powerful and while much good can come of it I am a touch concerned that we may become voluntary prisoners of our digital environments, which will appear like personal paradises and so entrap us. Think of the amazing new world of hologram glasses that awaits around the corner, which create a wondrous augmented reality. As this technology progresses, I imagine the underlying reality will become less interesting relative to the digital… Read more »

They’ve done research on the effects of a an electronically saturated early childhood. There’s a direct correlation between stunted emotional development and children being absorbed in “unreality”. Coupled with lack of even basic ethics and rising narcissism, selfishness is how we will increasingly live our lives. This augmented reality looks cool, sure. I, like you, have a concern for the future world. It has me reconsidering bringing another life into it because I feel we’re witnessing something huge take place and I don’t know if it would be fair to force another into similar circumstances. Your comment reminds me of… Read more »

Great stuff, Nick. I can’t help but think of the relationship between signs and simulations. Just like signs are meant to convey messages—messages which in many cases are untrue and/or unfulfilling—simulations offer the illusion of experience. The modern spectacle you write of seems to be one grand simulation. A simulation which promises emotional, physical, intellectual, and spiritual satiation—but hardly delivers. I’ve been wrestling with this a lot lately. In fact, my IG tagline is “None of this is real. The world is a representation.” So your article is timely for me. However, a while back I read this quote and… Read more »

This piece says a lot. Thank you for summarizing the problem about obsession with consuming images in our current age. I agree with the approach and general outline of the problem; and your proposed solutions are lovely. However, I have found myself thinking about interesting ideas in response to some little nuances of the text. Here are some rather alternative perspectives. Firstly there is a question about language. Complexity of vocabulary is presented as an indicator of “more complex” and elaborate discussion, and perhaps also, thought. I think the connection between language and thought is not necessarily positively correlated, which… Read more »

This piece says a lot. Thank you for summarizing the problem about obsession with consuming images in our current age. I agree with the approach and general outline of the problem; and your proposed solutions are lovely. However, I have found myself thinking about interesting ideas in response to some little nuances of the text. Here are some rather alternative perspectives. Firstly there is a question about language. Complexity of vocabulary is presented as an indicator of “more complex” and elaborate discussion, and perhaps also, thought. I think the connection between language and thought is not necessarily positively correlated, which… Read more »

Hi, a well researched and relevant article. I dislike the direction society has taken. I am ‘another’ person who has been squeezed out of the middle class, despite my education and initially resources. I have concluded if it can happen to myself, it can happen to anyone. I only say this on awareness of the kind of resources and apparent opportunity that were given to me. I suffer from overwhelming sense of emptiness and meaninglessness. Only recently, am I trying to remedy this situation. Yet, as a digital native, since 1992, most of my life has been spent online. It… Read more »

The Image-based society isn’t inherently bad rather it’s people’s willingness to just passively consume media as well as other people’s willingness to use those images to further greedy, capitalist ends. Images in film, television, the visual arts, and even some new media can be rather engaging, and can be used to communicate several powerful ideas and themes. Many artist throughout the ages have used the image to challenge the audience/viewer. However today as I said earlier many are too content passively consuming. Instead a shift must occur in which people actively engage and challenge the image. Thereby the image and… Read more »