“How’s it going?” “How are you?” “How’s life?”

We’re asked these questions all the time.

Most of us typically respond with something automatic and mostly meaningless: “pretty good,” “doing well,” “all right,” etc.

But what if, instead, we treated this common inquiry as an opportunity to remind ourselves of crucial, medicinal wisdom?

This is what I’ve started to do:

When people ask me how I’m doing, I usually say, “can’t complain.”

Now, you may be thinking: “can’t complain” is a pretty normal response to such a question; how is this not just another canned reply?

My answer is that it all depends on the spirit in which you deliver this reply, and whether or not you’re truly pursuing a “can’t complain” approach to life—or better yet, a Stoic approach to life.

Let me explain.

The Stoic Art of Rejoicing in Reality and Never Complaining

“What you’re supposed to do when you don’t like a thing is change it. If you can’t change it, change the way you think about it. Don’t complain.”

― Maya Angelou

When the late, great Maya Angelou penned these words, I wonder if she was aware that she was heartily agreeing with a bunch of thoughtful Greeks and Romans who lived about 2,000 years ago.

I’m referring, of course, to the group of ancient philosophers who came to be known as the Stoics.

The height of ancient Greek civilization, as depicted by Raphael: one of the first places I’d go if I had a time machine.

The Stoic school of philosophy was founded in Greece around 300 BC by a fellow called Zeno of Citium. Stoicism became popular in its time, flourishing for several hundred years as a way of life for people of diverse walks of life.

The Stoics are often construed as passive, cold, stone-like figures, but this is a misconception. In actuality, the Stoics were active participants in the world who thought we could use philosophy and reason to reach a state of everlasting tranquility, joy, mental fortitude, and excellence of character.

Today I want to discuss the Stoics’ perspective on complaining and thankfulness, to illuminate the power of a “can’t complain” philosophy of life. Let’s take a look at a few famous Stoics’ thoughts on complaining.

Epictetus

Among the most fundamental maxims of Stoicism is the idea that it is foolish and self-sabotaging to bemoan or worry about things which we cannot change, control, or influence. The Greek Stoic philosopher Epictetus put it this way:

“There is only one way to happiness and that is to cease worrying about things which are beyond the power of our will.”

Epictetus recognized that worrying, complaining about, and investing emotional energy into things we cannot change or control is a fast track to demoralization, depression, and burnout.

Conversely, he saw that focusing on things you can influence—your actions, habits, responses, projects, words, routines, thought patterns—is a kind of existential keystone. This approach actually changes things and fosters a sense of dignity, power, and vitality in the individual.

True empowerment begins when we direct our focus toward things we can affect.

Epictetus, 50 AD – 135 AD. (Source)

On a related note, Epictetus made the following comment on the nature of wisdom:

“He is a wise man who does not grieve for the things which he has not, but rejoices for those which he has.”

Epictetus saw that any time we complain about or grieve for things that are lacking, we’re refusing to celebrate this moment as it is—refusing to acknowledge our blessings.

And to really put things in perspective, consider this: Epictetus spent his childhood as a Roman slave, and he lived (most of) his life with a completely disabled leg, which was either disabled at birth or broken beyond repair by his slave master.

Dude had it rough as fuck. And yet, in spite of his unfortunate circumstances, Epictetus celebrated his life and went on to become one of the most popular and sought-after philosophers of his time. Kind of makes a lot of our modern “problems” like not having the money for a bigger apartment or new TV or [insert inessential thing here] seem petty and silly, right?

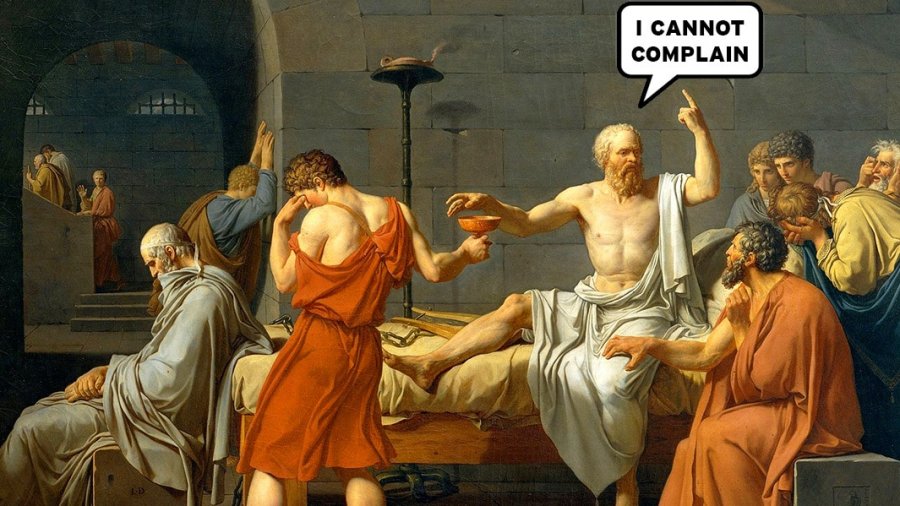

Seneca and Socrates

Consider also the deaths of Seneca, a Roman Stoic philosopher, and Socrates, the notorious Greek philosophical trickster and a precursor to the Stoics.

Both men were sentenced to death for largely-bullshit political reasons, and yet both accepted their fate with serenity. The calmness with which Socrates accepted his death is considered by some his final lesson for his followers to ponder. And Seneca is said to have scolded his weeping students at the time of his death, asking them, “What has become of your Stoicism?”

At the moment when these men would have been most justified in complaining and grieving the unchangeable, they did not. They accepted it with dignity.

Now, admittedly such feats are… a tall order. I wouldn’t expect to be a fraction as poised in the face of my own unjust execution, and I don’t think there’s anything wrong with weeping and grieving for the death of a loved one.

However, these stories are, to me, inspiring and instructive: If these philosophers were able to accept their own murders with tranquility, how many of our “misfortunes” and “problems” in modern life can we completely neutralize, with a bit of practice?

Marcus Aurelius

The renowned Roman Stoic “philosopher king” Marcus Aurelius, who in his life witnessed the deaths of several of his own children, summed up his thoughts on complaining when he wrote the following in his famous Meditations:

“Everything that happens is either endurable or not. If it’s endurable, then endure it. Stop complaining. If it’s unendurable… then stop complaining. Your destruction will mean its end as well. Just remember: you can endure anything your mind can make endurable, by treating it as in your interest to do so. In your interest, or in your nature.”

All I can think when I read this is: What a badass.

Marcus Aurelius recognized that complaining about misfortune is a distraction from the fundamental task at hand: to endure. If we direct our focus toward endurance, and tell ourselves that endurance is the best thing for us, we develop an almost superheroic ability to stand strong in the tides of fate.

Marcus Aurelius most likely penned Meditations while on campaign in Europe c. AD 170-175. (Source)

Diogenes

Finally, let’s ponder the words of the Greek Cynic philosopher Diogenes, another precursor to the Stoics:

“He has the most who is content with the least.”

Diogenes, as a practicing Cynic, led an ascetic life of extreme deprivation, living without a home, in the streets, cloaked in rags, eating and drinking only what was necessary.

Diogenes once said, “I threw my cup away when I saw a child drinking from his hands at the trough.” This guy was the polar opposite of a complainer; he was actively trying to learn how to be content with the bare essentials. In one of the greatest books I’ve ever opened, A Guide to the Good Life: The Ancient Art of Stoic Joy, William B. Irvine wrote the following of Diogenes:

“He believed hunger to be the best appetizer, and because he waited until he was hungry or thirsty before he ate or drank, ‘he used to partake of a barley cake with greater pleasure than others did of the costliest of foods, and enjoyed a drink from a stream of running water more than others did their Thasian wine.'”

It’s settled: Diogenes was a man who knew how to rejoice in life, despite living in what most of us today would consider intolerable, miserable poverty.

Diogenes Sitting in His Tub by Jean-Léon Gérôme

Like the Stoics who came after him, he understood that tranquility and happiness arise when we stop cursing the unchangeable or wishing for something different and instead start savoring simple joys and appreciating reality just as it is.

The Perennial Problem of Human Desire

Okay, so that Stoic stuff sounds pretty good, but how do you actually implement it? Easier said than done, right?

True.

A perennial problem faced by humans across the ages is that our desires cause us to be perpetually dissatisfied with what we have. As William Irvine put it in A Guide to the Good Life:

“We humans are unhappy in large part because we are insatiable; after working hard to get what we want, we routinely lose interest in the object of our desire. Rather than feeling satisfied, we feel a bit bored, and in response to this boredom, we go on to form new, even grander desires.”

We dream of getting a certain job, owning a certain home, marrying a certain person, but once we finally attain these things, we quickly start taking them for granted. We begin to form newer, bigger desires and dreams, forever focusing on the next destination.

We dream of getting a certain job, owning a certain home, marrying a certain person, but once we finally attain these things, we quickly start taking them for granted. We begin to form newer, bigger desires and dreams, forever focusing on the next destination.

Of course, when we do this, happiness never arrives. It’s always delayed, just out of reach—a carrot on a stick, with us as the donkey.

The techniques developed by the Stoics can be seen as a kind of toolkit for short-circuiting this process—for counteracting our innate tendency to always yearn for the next thing, instead of rejoicing in the many gifts the cosmos has already bestowed upon us.

Two Stoic Practices to Help You Rejoice for What Is

Let’s take a look at two techniques derived from Stoic teachings that can help us stop chasing ever-receding carrots and start loving what we already have.

Negative Visualization

“We should love all our dear ones… but always with the thought that we have no promise that we may keep them forever—nay, no promise even that we may keep them for long.”

— Seneca, Roman Stoic philosopher, 4 BC – 65 AD

Seneca, Portrait by Peter Paul Rubens (1577-1640).

Negative visualization is one particularly powerful Stoic antidote to the problem of human desire.

The idea is simple: spend time contemplating death and loss to appreciate all that you currently have.

Regularly spend time imagining how you would feel if you lost a loved one. Or your house. Or your job. Your money. All your possessions. All your opportunities. Your talents. Your health. Your family. Life itself.

For one, such a practice increases preparedness, resilience, and tranquility when shitty things do inevitably happen—because, of course, they do.

Beyond that, though, negative visualization increases joy and appreciation for what you currently have.

When you spend time deliberately realizing that nothing is guaranteed, that everything you love and cherish could be taken from you tomorrow by some sick twist of fate, you feel humbled. You realize how many gifts and blessings you truly have. You see the real worth of everything surrounding you.

This is an experience people commonly have on their deathbeds or after near-death experiences, but here’s a piece of advice I’m sure we can all agree on:

It’s a hell of a lot better not to wait until you’re on your deathbed to start having these realizations.

You don’t want to wait till you’re about to leave this Earth to realize how damn good you have it and start approaching your life with the gratitude it really deserves. You want to start doing that now. Yesterday.

Negative visualization can help you.

To start experimenting with this technique: Try, just a couple times per week, to reflect for a minute or two on how you would feel if something awful happened: Your house burns down. Your best friend dies. Your bank account gets emptied. You find out you have cancer. An apocalyptic event happens.

Such imaginings will undoubtedly seem morbid to some, but if you’re honest with yourself, I’m sure you can see that imagining these losses will dramatically increase your appreciation for the fact that there is much in your life that is precious to you.

Amor Fati: The Love of Your Fate

Amor fati, a Latin phrase meaning “the love of your fate,” is another practice worth mentioning here.

Born a slave, Epictetus still loved his fate. (Source)

The idea has been traced back to none other than our Stoic friend Epictetus, but the German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche (who resembled a Stoic in some ways) is the best-known proponent of this approach to life. In The Joyful Wisdom, Nietzsche wrote:

“I want to learn more and more to see as beautiful what is necessary in things; then I shall be one of those who makes things beautiful. Amor fati: let that be my love henceforth! I do not want to wage war against what is ugly. I do not want to accuse; I do not even want to accuse those who accuse. Looking away shall be my only negation. And all in all and on the whole: some day I wish to be only a Yes-sayer.”

And in Ecce Homo:

“My formula for greatness in a human being is amor fati: that one wants nothing to be different, not forward, not backward, not in all eternity. Not merely bear what is necessary, still less conceal it—all idealism is mendacity in the face of what is necessary—but love it.”

Amor fati is a practice of affirming and embracing literally everything that has ever happened or will happen to you, in recognition of the fact that all events leading up to this moment were necessary precursors to the precise world you’re standing in and the precise version of you that is reading this article.

You would not be the exact person you are without every single one of your experiences. Even the shittiest things that ever befell you—the times when you suffered the most—were necessary to forge you into your current self. And perhaps those times of suffering were actually more important than other times, considering that our suffering strengthens and deepens us in ways that nothing else can. As Nietzsche put it in The Joyful Wisdom:

“Only great pain is the ultimate liberator of the spirit… I doubt that such pain makes us ‘better’; but I know that it makes us more profound.”

Damn, Nietzsche.

*spine tingles*

Ahem, anyway… amor fati sounds cool, right? It’s basically a gratitude practice on superfoods. How to implement it, though?

Well, when we at HighExistence (another project of mine) built our self-actualization obstacle course based on Nietzsche’s “gymnastics of the will,” we devised an Amor Fati challenge.

In essence, the challenge is to write down three non-obvious things for which you are grateful, every day for thirty days. It’s basically like keeping a gratitude journal, but instead of writing down obvious things like health, family, food, and pets, you stretch yourself and find ways to be grateful for non-obvious or even seemingly awful things that happened to you. Examples might include:

- I am grateful that I was robbed because my family and I are okay, and this has lit a fire under my ass that will prompt me to start training in self-defense and take more thorough security precautions to protect us. The experience has also made me realize how fortunate I am that my family and I are healthy, safe, and prosperous.

- I am thankful for this freezing cold weather because it gives me an opportunity to become more resilient, and I know I will appreciate the spring and summer much more after experiencing several months of winter.

- I am grateful that Wendy broke my heart into a thousand pieces because I know my grief must be commensurate to the love that we shared, and I now understand the true value of love. I know I will become stronger through this experience, and I know that destruction breeds creation: within this ending resides an opportunity for a new beginning.

- I am not thankful that my friend died when he did, but I am thankful that he had to die at some point, because that means that he lived. Death and life are inseparable as Earth and sky. Death is the most natural of happenings and an essential aspect of existing at all. I see more clearly than ever that because we are mortal, because we are finite, our time is infinitely precious. This experience will make me rejoice in my loved ones, show and tell them how much I love them, and never take them for granted again.

A 30-day amor fati challenge is an effective way to kickstart this shift in perspective—this willingness to search for the silver lining in all things, to learn and grow from all experiences, and to appreciate our lives just as they are.

A formalized challenge is not a necessity, though. You can begin to cultivate amor fati by regularly pondering your obvious blessings and also pondering the hidden blessings buried in that which first appears to be pure horse shit.

And that brings us back to the power of not complaining…

Complaining is Anti-Gratitude

“Man only likes to count his troubles; he doesn’t calculate his happiness.”

― Fyodor Dostoyevsky

The commonality between Stoic negative visualization and amor fati is that both are practices of cultivating gratitude—thankfulness for What Is, rather than resentfulness for What Might Be or What Could Have Been.

You’ve probably caught wind of the pile of scientific studies attesting to the power of gratitude to improve our psychological health, physical well-being, relationships, and more.

There’s a simple reason for these findings: gratitude freaking works.

Life is way better with gratitude. Scientists are essentially confirming what the Stoics already knew 2,000 years ago.

Now let’s deconstruct what complaining is: complaining, in its extreme form, is quite literally a practice of being ungrateful for how things currently are and instead choosing to focus on and whine about everything you wish you could change.

It’s easy to see why the Stoic badasses of old would see complaining as nothing less than toxic poison for those seeking tranquility and the good life.

Complaining is the antithesis of Stoic teachings. It disempowers the fuck out of you by conditioning you to perceive misfortune and think of yourself as a sad, sorry victim of destiny. It distracts you from the actions you could take to actually change whatever you’re complaining about. And if what you’re complaining about can’t be changed, you’re doing that thing the Stoics cautioned against: foolishly and fruitlessly fretting about the unchangeable.

Scientists are catching up on this point as well: findings regarding neuroplasticity have shown that our brains “rewire” themselves based on our habitual thoughts and actions. Habitual complaining, whether internal or external, quite literally trains your brain to perceive flaws and bugs in your existence, rather than good things. Gratitude, naturally, does the opposite.

In his book The Power of Now, Eckhart Tolle dispensed a poignant and uncannily Stoic perspective on complaining:

“See if you can catch yourself complaining, in either speech or thought, about a situation you find yourself in, what other people do or say, your surroundings, your life situation, even the weather. To complain is always nonacceptance of what is. It invariably carries an unconscious negative charge. When you complain, you make yourself into a victim. When you speak out, you are in your power. So change the situation by taking action or by speaking out if necessary or possible; leave the situation or accept it. All else is madness.”

Change the situation, leave it, or accept it. All else is madness. Boom, checkmate.

Complaining not only traps you in an endless proverbial samsaric cycle of literally telling yourself that you’re weak and your life sucks and there’s nothing you can do about it, it infects everyone around you as well.

As Tolle notes, complaining “invariably carries an unconscious negative charge.” There’s always an emotional undercurrent of resentment, and this not only reinforces your own bitterness and depression but basically makes you a walking container of radioactive emotional waste threatening to spill its contents on anyone within earshot. Complaining drags others down with you and encourages them to fall into the same psychological black hole that you fell into.

On Healthy Venting VS Toxic Complaining

Now, am I saying that it’s never okay to tell someone about your problems?

No, that’s not what I’m saying.

Everyone needs to vent from time to time—to purge emotional baggage, “get things off their chest,” and to be heard and empathized with. This seems to be a deep human need, and I support it. I don’t think it’s healthy to keep everything bottled up inside, and if you’re going through some seriously desolate psychological territory, I absolutely encourage you to talk to a loved one about it and consider seeking out a compassionate professional to help you sort through whatever’s ailing you.

When I say that “everyone needs to vent from time to time,” though, the key phrase is “from time to time.” A healthy practice of intermittent venting can easily become a toxic habit of daily complaining about trivialities, if one is not careful.

But how do you know whether you’re healthily venting or toxically complaining?

Great question.

Near as I can tell, there are three major signposts to look for:

For one, consider frequency. If you’re finding something to “vent” about every single day, you’ve probably slipped into toxic habitual complaining.

Another thing to consider is the magnitude of the things you’re “venting” about. Seneca was on point when he said, “We suffer more from imagination than from reality.” It’s important to ask yourself if what you’re venting about is really a big deal, or if your mind is blowing things out of proportion. Some helpful questions to ask are:

- Does this actually change the overall trajectory of my life in any way?

- Am I still going to care about this one year from now? One month, even?

- Do I still have all of the people who are most important to me and the essential things I need to survive?

- Is this an ongoing issue that’s seriously affecting my long-term emotional well-being, or am I turning a minor isolated incident into a major catastrophe because I like attention and drama and am addicted to complaining?

Such questions are very clarifying. The third way to distinguish between healthy venting and toxic complaining is to note the perspective, tone, and attitude you’re taking toward your misfortune. Here’s an example of what healthy venting might look like when one has an ongoing issue with a difficult coworker:

“Yeah, I mean, I’m grateful for my job and overall I know I’ve got it pretty good, but Mark does just get under my skin. I feel irritated when he undermines my authority in meetings and when he arrogantly acts like every idea he has is solid gold. I guess I just need to take a deep breath and start trying to be more assertive. Maybe I’ll have to talk to him about this. I can always find a new job if I decide he’s just too much. Do you have any other suggestions for things I could do to make this better? Thank you for taking the time to listen.”

And here’s an example of what toxic complaining might look like in the same situation:

“Oh my God, Mark is such a fucking douchebag! He’s making my life a living hell. You won’t believe what he said to me today, he’s so fucking smug. God, why do these things always happen to me? Why am I trapped in this stupid fucking job? I can never catch a damn break.”

As you can see, the Healthy Venter has more self-awareness. They don’t lose sight of the good things about the situation when they’re expressing the negatives. They’re calmer and speak about how they feel in relation to the situation, rather than how someone is making them feel (as if they have no power). They’re thankful for whomever is listening to them, and their focus is on finding pragmatic solutions to the situation, rather than pretending the situation is hopeless and unchangeable.

The Toxic Complainer does the opposite: They play the victim, act like they’re powerless in the situation, catastrophize everything, get carried away by their emotions, generate false patterns to confirm their own idea that they’re Cosmically Unlucky, and ooze contagious resentment.

Admittedly these examples are dramatized and polarized to make the different approaches immediately apparent. In reality, the difference between healthy venting and toxic complaining is often more subtle. There’s a grey area in there, and it’s up to each person to determine for themselves when they’ve crossed the line. But again, it’s very useful to pay attention to these three items:

1. How frequently you’re discussing/thinking about perceived misfortunes.

2. The magnitude of the perceive misfortunes you’re talking/thinking about.

3. The perspective, tone, and attitude you’re taking toward your perceived misfortunes.

These are the breadcrumbs that will lead you to discover whether you’re just doing some healthy, appropriate venting or habitually spewing radioactive complaint-waste on every passerby.

Lastly, it’s also worth re-emphasizing that complaining doesn’t necessarily have to be externalized. How you talk to yourself internally matters just as much. You might be sparing those around you by not vocalizing your complaints, but if you’re constantly bickering in your own mind, you’re still polluting yourself.

And, look, if you’ve been reading this and thinking, “Holy shit, this is me. I’m a toxic complainer. I bicker, internally and externally, all the time…,” please know that this is okay. Most of us do this, to some extent—I know I’m far from perfect. We’re not Stoic sages, after all.

Recognizing and acknowledging a self-sabotaging habit is half the battle when it comes to changing it. So take a deep breath and pat yourself on the back: You’re doing just fine. If I’ve come across harshly in this article, it’s because I realize that people often need a bit of “tough love” to jar them out of a downward spiral.

It’s very difficult to overcome your mind’s innate tendency to perceive lack all around you and desire things you do not presently have. Again, most of us are caught in this trap, to varying degrees. As you work to free yourself, self-compassion is essential. Be gentle with yourself, laugh at your foibles, celebrate your victories, and don’t beat yourself up when you falter.

If self-compassion is an issue for you, consider taking our Buddha’s Secret challenge within our HighExistence course, 30 Challenges to Enlightenment (this link gives you 20% off).

Full Circle: The “Can’t Complain” Philosophy

Whew, that was a lot.

Give me a sec to catch my breath.

*deep breath*

Okay. Cool.

Now…

Let’s return to where we started and talk about the power of the unassuming act of telling someone you “can’t complain” when they ask you how you’re doing.

You may have a pretty good idea now of what I’m going to say.

When I tell someone I “can’t complain,” it’s a self-reminder of the important lessons I’ve taken from the Stoics on the poisonous nature of complaining and the importance of rejoicing in what is.

It’s a reminder to practice negative visualization and amor fati in order to remember that I truly can’t complain when I consider just how many blessings I actually have. To the contrary, when I really think about all I’ve been given and how I would feel if I lost everything I love, all I can do is rejoice and thank Nature for her many favors.

“Can’t complain” can likely function similarly for you.

Again, the beauty of it is that almost every day, people ask us how things are going as a common social courtesy. This is a built-in environmental trigger that can prompt us to make a daily habit of practicing thankfulness.

A humorous irony in this is that to most people, “can’t complain” will just sound like another canned, default response to a canned, default question. But internally you’ll know it means much more.

You’ll know it is a profound reminder and affirmation:

I cannot complain.

I will not complain.

I will remember all I’ve been given.

I will rejoice in The Way Things Are.

Follow Jordan Bates on Facebook and Twitter.

Recommended Reading: A Guide to the Good Life: The Ancient Art of Stoic Joy by William B. Irvine

“Begin at once to live, and count each separate day as a separate life.”

— Seneca

Stoicism probably isn’t what you think it is. When we think of the Stoics, we tend to think of emotionless creatures trudging through life in a state of passive indifference, perhaps even pessimism. In this remarkable and highly readable introduction to Stoicism, William B. Irvine takes a hammer to this myth, illuminating an entirely unexpected portrait of Stoicism as a philosophy of tranquility, mental fortitude, joy, and appreciation in the face of life’s inevitable shit storms.

This is a book I’m currently reading, but I can already tell it’s one I’ll never forget. It’s inspired me to begin simultaneously reading Marcus Aurelius’ famous Meditations, and to eagerly await the day I crack open Seneca’s Letters From a Stoic and Epictetus’ Enchiridion. It’s already abundantly clear to me that Stoicism is an approach to life that will have a lifelong impact on me. It’s so simple, yet so wise and pragmatic: its emphasis on self-mastery and discipline, rejoicing in our blessings, and focusing on what we can control resonates deeply with recent (re-)realizations of mine about the vital importance of healthy long-term habits of body and mind. I cannot recommend this book enough to anyone who wants to live a more serene and contented life.

(Purchase it via Amazon or read the key insights in 15 minutes for free with Blinkist.)

“And when asked what he had learned from philosophy, Diogenes replied, ‘To be prepared for every fortune.'”

— William B. Irvine, A Guide to the Good Life

A version of this essay was first published on HighExistence.

About Jordan Bates

Jordan Bates is a Lover of God, healer, mentor of leaders, writer, and music maker. The best way to keep up with his work is to join nearly 7,000 people who read his Substack newsletter.