Around midsummer of this year, I was undergoing an inexplicable spell of irrational guilt.

These types of episodes have come to me before, but they’re infrequent, thankfully. What happens is this: some tiny aspect of who I am or a deed I’ve done (or have failed to do) bubbles up into my consciousness, and for one reason or another, I become ultra-fixated on it and begin to silently condemn myself.

These patterns of thought don’t (or never have) resulted in full-blown self-loathing, but they gradually erode my self-esteem and self-efficacy. Suffice to say that they aren’t fun and I hope they leave me the hell alone in the future.

Artio by Alexandra Nereïev. Photo Credit: Wiki Commons

How Our Brains Muck Things Up

I think a lot of us probably experience this mental tribulation to varying degrees in our lives. By my estimation, it’s a form of anxiety: anxiety of identity. We wonder if we’re good people, if we’re worthy of love and happiness.

Many of us are great at finding reasons why we aren’t good and worthy, or why we’re worth about as much as steaming, stinking sewage on a hot summer’s day.

This, in part, is due to consumerist culture’s endless attempts to convince us that we’re ugly, lacking, chunky, broken, unstylish, boring, and outdated (but don’t worry; they can fix you for juussttt $19.95!).

But furthermore, I think our anxiety of identity also stems from the fact that we, as humans, are hardwired to draw conclusions about people or situations based upon a few bits of information. This is often a helpful hunk of mental machinery, but in the context of measuring the value of ourselves and other people, it’s pretty freaking destructive and misguided.

Humans are remarkably complex and thus cannot be adequately characterized by a few or even a few hundred pieces of information. But our brains lead us to think otherwise — to make snap assumptions and to reduce people to single terms like “asshole”, “trashy”, “slut”, “douche”, “tree hugger”, “nerd”, “prude”, “druggie”, “Jesus freak”, etc.

This is a nasty phenomenon that has caused immeasurable grief and division throughout the history of humanity.

But as I alluded to, our brains can just as easily turn their awful powers of simplification and reduction inward, upon who we are. Single aspects of our lives can become magnified, and we can begin to convince ourselves that we are nothing more than fat or evil or lazy or dumb or what have you.

We need to guard against this type of thinking. It’s miserable and defeating and about as useful as politicians. Okay, okay, that was wrong to say. Most politicians.

Some basic ways we can avoid these trains of thought are: cultivating more awareness of our thought traffic, practicing conscious breathing, and meditating regularly.

When I was hit with that storm of irrational guilt this summer, I did those things, and eventually the thoughts and feelings subsided. But there was something else that helped me too — one man’s powerful statement about my identity.

Enter Kahlil Gibran

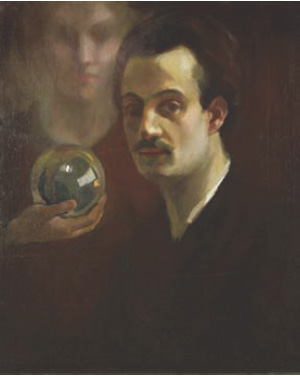

Self-portrait by Kahlil Gibran, circa 1911. Photo Credit: Wiki Commons

A friend had given me a copy of the short book, The Prophet by Kahlil Gibran several months prior, and I decided one day to jog to a nearby fountain, sprawl out, and give it a read. This was during the period when I was still experiencing the fixated thoughts and guilty feelings.

For those unaware, Kahlil Gibran was a Lebanese artist, poet, and writer who died in 1931. He is the third best-selling poet of all time, behind Shakespeare and Lao Tzu. The Prophet is his most famous work. It surged in popularity during the counterculture movements of the 1960s and has been read widely since.

So I was lying down, reading and enjoying the beautiful, poetic prose of The Prophet, when I came to a passage that chilled me to the core. I read and re-read a certain sentence, tears welling gently in my eyes. I had the rare and wonderfully intimate experience of feeling that the words had been written just for me. Such moments are what compel me to continue to read until the day my heart ceases to glug-glunk.

Here is the passage in full:

“And one of the elders of the city said,

Speak to us of Good and Evil.

And he answered:

Of the good in you I can speak, but not

of the evil.

For what is evil but good tortured by its

own hunger and thirst?

Verily when good is hungry it seeks food

even in dark caves, and when it thirsts it

drinks even of dead waters.You are good when you are one with

yourself.

Yet when you are not one with yourself

you are not evil.

For a divided house is not a den of thieves;

it is only a divided house.

And a ship without a rudder may wander

aimlessly among perilous isles yet sink not

to the bottom.You are good when you strive to give of

yourself.

Yet you are not evil when you seek gain

for yourself.

For when you strive for gain you are but

a root that clings to the earth and sucks at

her breast.

Surely the fruit cannot say to the root,

“Be like me, ripe and full and ever giving

of your abundance.”

For to the fruit giving is a need, as re-

ceiving is a need to the root.You are good when you are fully awake

in your speech,

Yet you are not evil when you sleep while

your tongue staggers without purpose.

And even stumbling speech may strengthen

a weak tongue.You are good when you walk to your

goal firmly and with bold steps.

Yet you are not evil when you go thither

limping.

Even those who limp go not backward.

But you who are strong and swift, see that

you do not limp before the lame, deeming

it kindness.You are good in countless ways, and you

are not evil when you are not good,

You are only loitering and sluggard.

Pity that the stags cannot teach swiftness

to the turtles.In your longing for your giant self lies

your goodness: and that longing is in all of

you.

But in some of you that longing is a

torrent rushing with might to the sea, carry-

ing the secrets of the hillsides and the songs

of the forest.

And in others it is a flat stream that loses

itself in angles and bends and lingers before

it reaches the shore.

But let not him who longs much say to

him who longs little, “Wherefore are you

slow and halting?”

For the truly good ask not the naked,

“Where is your garment?” nor the house-

less, “What has befallen your house?””

What is the Central Message?

“You are good in countless ways, and you are not evil when you are not good.”

I read this sentence again and again, was overwhelmed by it. It was so freeing, and I felt so grateful that this man — this far-off fellow who died 60 years before I was born — had existed and shared his writing with the world.

“In your longing for your giant self lies your goodness: and that longing is in all of you.”

In that moment, I felt that it was in all of me. I realized that my occasional obsessiveness over whether or not I am a good person arises from my mighty and fathomless desire to be a good person, or, the “giant self” that I sense resides somewhere within me.

What Gibran seems to be saying is that human beings are good because each of us, in the depths of our being, longs to become this “giant self”, this purely good version of ourselves. “Giant self” is a somewhat ambiguous metaphor. For me, it evokes images of the entire universe, or of pure love and kindness, or of our fullest potential.

We long to become the equivalent of demigods dancing amongst the stars. In this longing, though, our downfall is born. “For what is evil but good tortured by its own hunger and thirst?” Gibran writes. In this line, he suggests that our longing for vast goodness and love is so great that it becomes a tremendous burden upon us.

We, being confined to our animal bodies on our small rock of a planet, dream of being everything and of being flawless. But we can never reach that ideal, so we grope about and grow frantic and sometimes timid in our condition. We falter, seek pleasure and solutions in dark caves, emerge again into the light, and falter once more.

Gibran seems to theorize that it is our human fate to undergo this cycle of stumbling, regaining composure, and stumbling again. And, he says that some of us stumble more than others.

However, his crucial message is that our inevitable stumbling — our lamentable detours into that which is not good — does not at any point make us evil.

He seems to suggest that what we perceive as evil acts would be more accurately described as the temporary and inevitable bouts of not-good-ness in human existence.

To some, this might just seem like a clever word game, but I think Gibran is making a subtle and important distinction. To me, he’s saying that because it is in our inescapable nature to be not good some of the time, we are not justified in condemning ourselves for acts of not-good-ness, because it was always certain we would slip up.

We might be justified in saying that the very existence of this trap of darkness is, in itself, what is evil, but we are not justified in placing such a label upon individual people — such a move would be akin to calling a lion evil for killing an antelope, for Gibran.

Feeling bad about a mistake is healthy insofar as it prompts us to notice we did wrong, learn from the experience, and endeavor to do better in the future; anything beyond that is unnecessary self-crucifixion. You are not a bad person. You made a mistake. Learn from it. It’s okay. I forgive you. Forgive yourself.

Heavy Stuff, Man: Free Will and Opposing Forces

If we’re destined to not be good some of the time, where does that leave us with regards to free will?

Personally, I intuit that Gibran would say that we do have free will to choose the darkness or the light in any given situation. However, the seeds of inevitable stumbling are sewn in the fact that we are faced with countless decisions. No single decision is destined to go south, but at least a portion of all of our decisions must, because there are so many and because this is the nature of human life.

At the same time, one might also point out that it seems we are likewise destined to walk in the light for at least some of the time. Because of this, should we call ourselves good, as Gibran does, or would we be more accurate to simply say that the existence of the light is what is good?

This, I cannot say. It seems that Gibran takes an optimistic approach in implying there is goodness inherent in our longing. He may have done this to simplify his philosophy for everyday understanding or in order to more fully inspire those who would read his work. I digress.

Ultimately, from the above passage, I conclude that Gibran believes that mankind is, in a sense, innocent as children, but that we are caught up in an age-old tension between what is good and what is not good, the dance of the yin and yang, the opposing but interconnected forces of the human mind and perhaps, the universe itself. We should reach for the good, yet understand that the not-good is unavoidable.

I am reminded of a quote by Dostoyevsky:

“The awful thing is that beauty is mysterious as well as terrible. God and the devil are fighting there and the battlefield is the heart of man.”

Come Hither, Skeptics

For some people, Gibran’s message may seem unrealistic or flat-out incorrect.

I’ve previously encountered and been intellectually tantalized by the argument that the concepts of “good” and “bad” or “evil” are nothing but constructions of the mind that we assign to things as a means of processing and understanding the world.

So, let me be the first to admit that I don’t take Gibran’s words for gold or assume they’re universally true. I’ve questioned them and mulled them over.

In writing this post, I examined my beliefs regarding concepts of “good” and “evil” in the universe, and this is what I found: I am undecided on the matter.

On one level, as I said, the idea that “good” and “evil” are constructions that exist solely within our minds and are not inherent elsewhere in the universe has appealed to me in the past, and still does to an extent.

On another level, the metaphysical idea that I mentioned in the context of Gibran’s work — the balance or tension of opposed forces of good and evil (very similar if not identical to the Taoist and Buddhist conception) — strikes me as containing an important truth, even if such forces only exist in our minds.

On a final level, I must mention that I have, on many occasions, felt with the purest of conviction that there is some sort of essential and unifying goodness in the order, beauty, and mystery of the universe, something worthy of my deepest love, respect, and admiration. In other words, I’ve felt that the universe is inherently good.

People have debated this philosophical issue for aeons and will continue to, so please, be as skeptical as you like. However, I’ve come to the realization that the “true” answer to the question, whatever that even means, is not that important to me.

Well, What is Important, Then?

In my mind, it is paramount to understand that “good” and “bad” or “good” and “evil” are deeply engrained in our consciousness. Regardless of their true nature, these concepts are alive in our noggins and color our perception, for better or worse.

Because this is the case, it seems most pragmatic to focus on our individual subjective consciousnesses. The things that make life look better and brighter consistently — those are, for our purposes, good things to continue doing or exposing ourselves to. And the things that cast shadows upon our days — work to eliminate them, knowing full well that they can never be fully eradicated.

In this vein, what matters to me about Gibran is that his poetic musings resonated with a deep part of my being and led me to a better place. What is important to me is anything that proves to be useful, illuminating, and/or uplifting in both my glad and dreary hours.

My reaction to his words was one of the most powerful and visceral that a book has ever produced in me, and it was integral in guiding me away from a place of fear and anxiety.

I felt his message being whispered from the grave, and in that moment, the feeling was more real and true than any thought could ever be. Too often I think we ignore our intuition and felt experience in favor of “facts” that we accepted long ago. I humbly submit that we should not.

Your felt experience will, more than any amount of thinking and pondering, lead you to understand who you are, what drives you, what moves you, what satisfies you, what you love, and what you will fight for. Understanding these things is not something that we should take lightly. Our (mis)understanding of ourselves and our place in the universe can liberate or annihilate us.

We must strive to find the balance. Use and cherish your rational powers, but in doing so do not forget that sometimes your heart and feelings know things that your mind never will.

If you find yourself in an hour of darkness, perhaps Gibran’s words can be the candle-fire for you that they were for me. Perhaps, if nothing else, you can find solace in knowing and remembering that he and I and many others have thought the following to be true:

“You are good in countless ways, and you are not evil when you are not good.”

P.S. I strongly recommend The Prophet to all of you. For a short book, it has many moving and poignant passages. You can buy it here. Note that if you click the hyperlink to Amazon from my site and buy a book, I receive a fraction of the cost, as I am an Amazon affiliate. If you do, I truly appreciate your support.

Also, if you enjoyed this essay, I’d love for you to share it on Facebook and/or check out the ways to get free updates from me.

Photo Credit: qthomasbower

About Jordan Bates

Jordan Bates is a Lover of God, healer, mentor of leaders, writer, and music maker. The best way to keep up with his work is to join nearly 7,000 people who read his Substack newsletter.

One of the best books ever. Worth rereading dozens of time. And good insights on “good” and “evil” and trusting our intuitive sense.

Ryan,

Thanks for commenting, and I’m glad you found my thoughts to be on-point. I’m with you — the lucid and simple wisdom presented in ‘The Prophet’ is just plain wonderful. It’s one book that I want to always have for reference and to re-read again and again.

Jordan, I have much to say on this post as I have also walked along the river of guilt and at times drawn deeply from it’s tantalizing waters… Rather than diving too deeply into some of the profound questions you’ve presented here (which I can expand on later if you’d like), I’ll just share my thoughts on the central question you’re working through: good vs evil. As you’ve stated, do “good” and “evil” really exist, or are they only in our minds? To me, they are merely a point of view, and although the actions and ramifications still exist, you’re… Read more »

Derrick, Thanks for this insightful and in-depth comment. I’m sure a lot of people will benefit from reading it. We certainly share similar views, especially with regard to the idea that our most painful experiences can often be our most useful catalysts for personal growth. I wrote at length about this idea in an essay a while back: ‘The Impossibility of Traditional Happiness (And How We Must Re-Define It)’. Perhaps you or someone else would like to read it sometime, so I’ll leave the link: http://www.refinethemind.com/re-define-happiness/ I personally don’t, in my conception of life, believe that everything that happens to… Read more »

1) I absolutely loved “The Prophet”. It had a huge influence upon me in my little life.

2) guilt… is it actually guilt or is it self exploration? To understand, to measure, to probe… to ask?

Francis,

1) Yes! So glad you love “The Prophet” as well.

2) To probe our past experiences, to ask questions and try to understand them–that is certainly self-exploration. But to condemn ourselves–that, I think, is guilt/remorse/shame.

And therefore…all bad? Negative? In your own words above, you accept that getting it wrong is entrenched in Man’s Nature. Look at it another way: If somebody asked you “How Many Great Loves are there, and where do YOU feel YOU stand on each one of those?” How would you answer? My tiny mind struggles with that, but would probably say: “Errr…three?”. (Love of God, how ever you perceive Him or Her; Love of Man, Love of Self). And which one do I struggle the most with? Many people would say: “Well, I’m an Atheist, therefore the Love of God… Read more »

Francis, thank you for the insightful comment. I love what you take away from Gibran as important. The good-humored, quiet acceptance. I want to clarify that I don’t think all guilt/remorse/shame is necessarily a “bad” thing. I think it can be a sign of conscience and a catalyst for better future behavior/inner strength/positive change/etc. However, I do think that (especially in a society based upon making us feel guilty for what we aren’t doing and who we aren’t being) it’s very easy to feel guilt for things that we shouldn’t feel guilty for, or to condemn ourselves excessively for something… Read more »

1) I like Huxley’s quote. Witty.

2) “(Especially in a society based upon making us feel guilty…etc)” Um. Don’t you also see rampant Hedonism?

Right. I see the hedonism and guilt-tripping existing simultaneously.

The hedonism seems in part reactionary—a by-product of so many decades of repression. Or it might just be human nature. There still seem to be plenty of structures in place to convince us to be ashamed of our actions.